Article by Tom Steele

The Bradford printing firm of Percy Lund Humphries became one of the leading publishers and printers of books of and about contemporary art in the twentieth century. Here I try to understand how a Yorkshire printing company progressively pursued technological improvements in photography and printing while maintaining a minor interest in local papers, The Ilkley Free Press, rambling, antiquarianism and Theosophy came to be at the forefront of aesthetic modernism in Britain. [1]

My initial query was why Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Theosophical text, Thought Forms, which was so influential on the Northern European early abstract expressionist painters like Kandinsky, Mondrian and Malevich, had been published in Bradford by Percy Lund Humphries in 1901. Was Percy Lund, the founding Director of the firm, involved with occult theory through Theosophy and was there a connection between the new technological advances in photography and colour printing and the emergence of abstract painting?

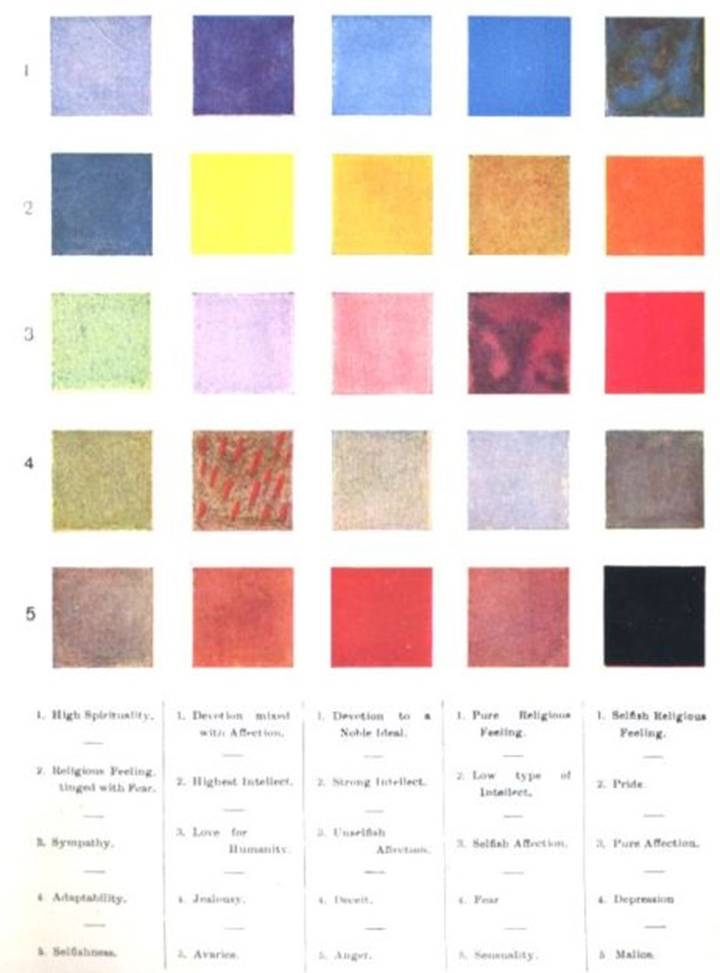

I was impressed by the quality of the colour reproductions of so-called ‘thought forms’ and the grid of colour/emotion in the frontispiece to the text (see illustration) and wondered whether there was any connection between the ability mechanically (a la Benjamin) to reproduce colour forms in this way and the move towards pure non-representational abstraction in painting. [2]

Did the new technology and advances in photography influence choices painters made about their creative work? Photography was, for example, increasingly capable of reproducing natural phenomena in ways that appeared to be aesthetically pleasing. Portrait painting was threatened by photographic ‘realism’ while ‘Landscape’ and perhaps especially urban scenes were being captured dramatically by the camera, which ‘never lies’, often for documentary reasons. [3] See also the related development of moving images by Louis le Prince in Leeds and some of the first cinematic film. [4]

Did the new technology and advances in photography influence choices painters made about their creative work?

Fig 1.

Frontispiece to Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought Forms charting colour to emotion (note the black square labelled ‘Malice’ which may have appealed to Malevich a few years later).

Fig 2.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s An Organic Architecture, 1939

Percy Lund was indeed a prominent Theosophist in Bradford where he founded the society’s Minerva Lodge. He wrote and lectured on Theosophical issues throughout Britain and must have known Besant and Leadbeater.

Similarly, advances in colour printing especially the invention of the tri-chromatic processes at the end of the nineteenth century were making it increasingly cheap to make fine colour reproductions for art journals and magazines, which were being widely circulated among a growing public for affordable high-quality reproductions of art works, and ‘art appreciation’ generally – the rapid growth of the market for the private and domestic consumption of ‘Art’. In the face of this technological advance and mass proliferation of images, did ‘Art’ need to be re-enchanted?

So, in summary, were local advances in colour printing, photographic technology and image reproduction, alongside the emergence of the Theosophical movement - as a widespread quasi- religious cult of consciousness evolution of belief in ‘underlying realities’ that could be expressed and communicated by the artistic illuminati or adepts - somehow connected in the industrial heart of Yorkshire at the turn on the twentieth century? Percy Lund was indeed a prominent Theosophist in Bradford where he founded the society’s Minerva Lodge. He wrote and lectured on Theosophical issues throughout Britain and must have known Besant and Leadbeater. [5]

He was also involved with the Bradford Arts Club which at one time shared rooms with the Theosophical Society (as was also the case in Leeds). Lund was co-founder of Percy Lund, Humphries and Co (PLH) in 1895 with Walter Humphries and from the outset invested in new typefaces, design and technical innovation. Acutely aware of the burgeoning professional field, PLH acquired The Penrose Annual in 1897 for its reviews and exemplification of advances in colour printing and photography. PLH pioneered monotype machines, the use of half-tone and, eventually, offset lithography, rapidly becoming the first-stop firm for high quality photographic reproduction and printing.

In the immediate post-World War Two period, the firm was co-managed by Peter Gregory the founder/funder of the Gregory Fellows at the University of Leeds (supported by Bonamy Dobrée, Herbert Read, Henry Moore and TS Eliot) and with Read and Roland Penrose, the ICA in London. He was at the very centre both of nurturing a public taste for ‘Modern Art’ in Britain and furthering the careers of Britain’s own practitioners such as Moore Hepworth and Nicholson.

He established an office for PLH in Bloomsbury, whose basement studio for a while housed the photographer Man Ray, and design artist McKnight Kauffer, which welcomed modernist artists and trends from Europe and the United States . In 1939 PLH published Frank Lloyd Wright’s lectures at the Royal Institute of British Architects, verbatim, as An Organic Architecture, the book that marked the real beginning of the firm’s publishing activities.

This direction was consolidated a few years later by what was probably the most daring major investment in the work of living artist yet, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, introduced by Herbert Read (1944).

Thus PLH represented a kind of ‘Northern Powerhouse of Art’ in which Yorkshire artists like Moore and then Hepworth were the vanguard, their work given a decisive discursive legitimacy by fellow Yorkshireman, Herbert Read. Read’s elegant prose suggested a deeply ‘spiritual’ meaning to their art which connected it both to landscape and to what Kandinsky and the Theosophists might have called ‘innerer Klang’, the soul’s music. [6]

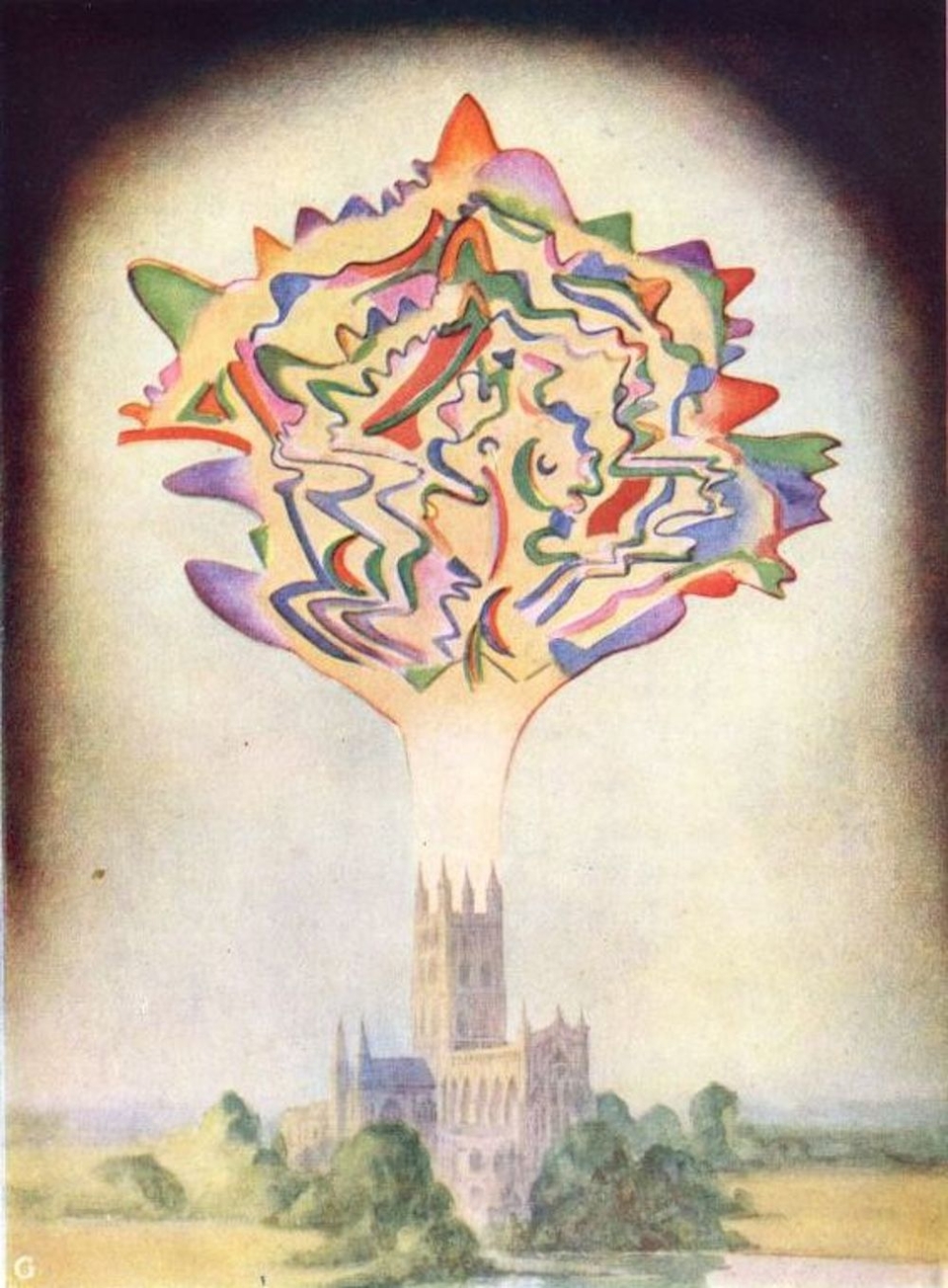

Comparison of illustration from Thought Forms with a Kandinsky abstract painting of 1913 sent to Michael Sadler in Leeds shortly after completion.

In 1939 PLH published Frank Lloyd Wright’s lectures at the Royal Institute of British Architects, verbatim, as An Organic Architecture, the book that marked the real beginning of the firm’s publishing activities.

Fig 3.

‘Thought-form of the music of Charles Gounod’ from Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought Forms (1901)

Fig 4.

Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913

So how do we account for these subtle movements from the provincial to the international stage? Percy Lund seems to have been a deeply religious man but perhaps not in a conventional sense and took a lifelong interest in Theosophy. Steve Lightfoot thinks that he may have been influenced by Rev Thomas Rhonnda Williams who was pastor of the Greenfield Congressional Church and a staunch supporter of the Labour Party, standing, unsuccessfully, in the 1918 election in Cambridge.

Williams lectured frequently on Besant and perhaps as a consequence of his influence Lund published a number of books on Theosophy including the ABC of Theosophy in 1891 written by Henry Snowden Ward, Karma and its twin doctrine of reincarnation, and The Key to Theosophy' in 1893 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Lund also published a number of books by Williams in 1901, 1904, 1905 and 1907. [7]

Many believed that experimental developments in photography, X rays, radio waves, psychology and such like revealed the effects of hitherto unrealised subtle forces.

But the West Riding of Yorkshire had for some time been a hotbed of radical Spiritualist activity since it arrived in Britain from the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. [8] David Lund, who may have been Lund’s cousin, had founded an occult sect called The Society of Dew and Light (or The Dew and The Light) in Keighley, which seemed to have upset Samuel Mathers and the founder of Theosophy, Madame Blavatsky . There was a fusion of Spiritualism and industrial communalism inspired by Robert Owen which increasingly led to radical political activity that ultimately contributed to the foundation of the Independent Labour Party in Bradford in 1894. [9]

There was also a marked ‘scientific’ tenor attaching to Spiritualist beliefs. Many believed that experimental developments in photography, X rays, radio waves, psychology and such like revealed the effects of hitherto unrealised subtle forces. In France, for example, the photographer Hippolyte Baraduc was convinced that the psychic energies of spiritual adepts could be manifested materially and devised a series of experiments using photographic plates. The resulting images of auras and cloud emanations he believed captured in some way the very soul of the adepts. [10] Marina Warner makes the acute observation that, although Baraduc considered his work deeply scientific, his ‘images of soul and thought are strange and captivating as acts of imagination and art. In their minimal non-figurative and gestural style, they have become unwitting examples of early expressive abstraction’ (Warner: 260). [11]

Her phrase ‘expressive abstraction’ is telling. It emphasises the in inwardness of what was to become a significantly different form of abstract art from that which starts from the representation of external objects. Warner notes that Baraduc owed much to the idea of the astral body then being developed by Theosophists like Besant and Leadbeater: ‘Leadbeater and Besant attempt to establish a system of natural values for colours, strokes, and shapes, through a series of booklets, still in print’(Warner : 261). Indeed, the first of these booklets were, as we have seen, published by Percy Lund Humphries in Bradford in the late nineteenth century.

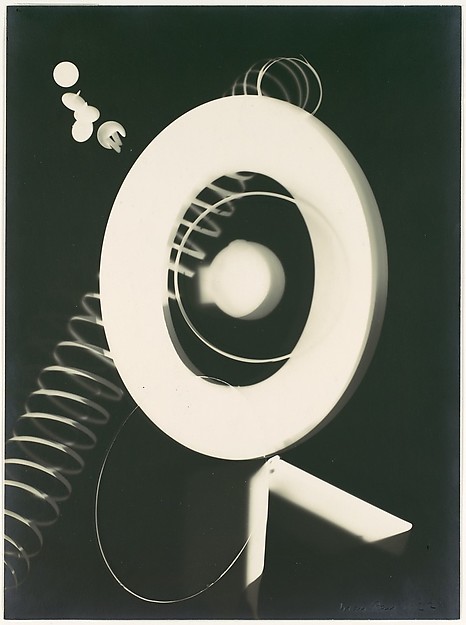

Warner’s illuminating discussion of the influence of these kinds of photographic and colour experiments in capturing ‘thought forms’ shows how they endured well into the twentieth century running through the Bauhaus in the 1920s (where Kandinsky appears to have kept a copy Thought Forms close by) and as late as the 1960s influenced Andy Warhol’s icons of stars and powers ‘building on accidents caused by printing out of register and emblazoning his subjects’ outlines with Kirlian style aureoles of different metallic hues’ (Warner: 263). [12] In PLH’s basement studio in Bloomsbury, Man Ray’s ‘Rayographs’ ‘revealed a new way of seeing that delighted the Dadaist poets who championed his work, and that pointed the way to the dreamlike visions of the Surrealist writers and painters who followed.’ [13]

Marina Warner makes the acute observation that, although Baraduc considered his work deeply scientific, his ‘images of soul and thought are strange and captivating as acts of imagination and art.

Fig 5.

Man Ray, Rayograph, 1927

There is reason to believe that Percy Lund was equally deeply attached to these ideas and, indeed, with his friend Henry Snowden Ward created a series of photographs of people and places that exhibit curiously ‘uncanny’ atmospheres. But he was also an acute businessman who harnessed the most advanced technology of the day to improve the crafts of photography and printing. He retailed the St John’s camera, installed the revolutionary Lanston Monotype text composition printing system from the USA, enhanced colour half-tone printing, effectively improving economy and quality. [14]

The acquisition of The Penrose Annual in 1897 and publication from 1907, transformed it into the bible for photographers eager for new equipment and techniques as well as printers anxious to release graphic design from its subservience to technical process. Leading designers and printers such as Stanley Morison and Jan Tschichold would design the Annual and showcase the latest in typographic style.

Bradford was, of course, not at all the provincial backwater of music-hall jokes and T S Eliot’s mocking silk-hatted millionaires, but a thriving wool town, producing much of the world’s worsted cloth. It had enviable public buildings including its Florentine Town Hall that attracted Ruskin’s attention, an exemplary model factory town in Saltaire producing high quality alpaca wool and Donskoi cloth, and an appetite for technological innovation and political reform – see W E Forster’s Education Act of 1870, Margaret Macmillan’s pioneering work with young children and the founding of the ILP. Moreover, Bradford housed a significant community of German Jews in ‘Little Germany’ which invested heavily in the political, economic, philanthropic and cultural life of the town.

Remarkably secular in approach, with no Orthodox synagogue until the turn of the century, this liberal community was in many respects an important conduit of European Enlightenment thought and culture. [15] At the core of this, artistically, was the Rothenstein family. William Rothenstein was a fine painter, closely connected with experimental currents and patrons in Paris. He became an important moderniser at the Royal College of Art in the 1920s when, for example, he encouraged Moore and Hepworth to study with Eric Gill.

Leading designers and printers such as Stanley Morison and Jan Tschichold would design the Annual and showcase the latest in typographic style.

His son, John, was pivotal in 'dragging the British art world screaming and kicking into the twentieth century', as his obituary in The Independent stated. [16] His brother Albert, who anglicised his name to Rutherston in 1916, was also a painter closely involved with the Camden Town Group, Augustus John, William Orpen and the London avant garde. The third brother Charles (later Ruthersden) had one of the finest collections of contemporary painting and sculpture in the North and generously lent it out for exhibition. He was a key figure in Bradford’s Arts Club founded in 1902 which touched off the brilliant Leeds Arts Club the following year. His enthusiasm for art and especially sculpture was infectious: Henry Moore wrote that it was Rothenstein who introduced him, then relatively unknown, in 1923 to a man who was to become a close friend and signally important to his career, Eric Craven Gregory, better known as Peter Gregory. [17]

Moore recalled an ‘acquaintanceship that grew slowly into what was to be the closest friendship of my life’, concluding ‘there are few men who have done so much, so modestly, for young living artists’. [18] Holman notes: ‘It was Gregory who offered Anton Zwemmer extended credit to cover the cost of printing the first book on Moore in 1934 and, in 1944, Gregory who both printed and published Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, the book that launched the Complete Sculpture in six volumes.’ [19]

Appropriately, the next phase in the PLH story really begins with Peter Gregory, who with Eric Beresford Humphries established PLH as probably the leading fine art publisher of its day, encouraging a wealth of new British talent, producing monographs of European modernist artists and consolidating the reputations of the Yorkshire sculptors Moore and Hepworth as well as Ben Nicholson. [20] Gregory and Humphries (who was the son of Percy Lund’s partner Edward Walter Humphries) were appointed Joint Managing Directors in 1930. While Humphries remained in Bradford to direct the actual publishing operations, Gregory established the London office and built up a network, and often a concerned patronage, of leading avant-garde and frequently impoverished artists. He appointed McKnight Kauffer as the company’s first Design Director and, as we have seen, the basement studio space was shared with Man Ray. The office saw frequent visits from continental artists.

Charles Lubelski notes the remarkable shift that takes place in the firm at this time:

Humphries and Gregory were very much aware of the ‘new thinking, new ideas,’ typographically and in creative design emanating from a war ravaged Europe. Both were sensitive to the new art movement – so-called ‘Modernism’; but more importantly they were keenly aware of the economic advantages of putting into practice modern design and typography into a printing industry long constricted by Victorian mores and values. Their focus was to be modern typography, creative design and high end art publications of both acclaimed and non-populist artists. And to achieve this ambition meant nothing less than the highest quality graphic repro technology combined with perfect printing techniques. [21]

Humphries concentrated closely on typography and production values, so that the artists themselves would often supervise the process – Moore, for example, preferred the older letterpress process over lithography as it produced a denser image and he would sketch the works while waiting for proof corrections. The typographic designer, Jan Tschichold (ejected from Germany by the Nazis as a ‘cultural Bolshevist’) produced new typography for the Penrose Annual in 1937.

However, Lubelski quotes Tony Bell, a former director at the company, as noting: ‘ “Something of the spirit of the Bauhaus rubbed off in our composing room, even before the arrival in our midst of Jan Tschichold, the high priest of asymmetry.”’ Lubelski continues, ‘Many of these typefaces were of a sans serif nature, which complemented the new austere Spartan angular geometric forms. [22]

Following a temporary drafting into the Ministry of Information during the WW2 Gregory became Chairman of Lund Humphries in 1945. [23] The firm had prospered during the war years as a publisher of government information for the HMSO and PLH were swift to benefit from WW2 technical developments like cellulose and polyester film materials and aluminium and magnesium plates - as well as stocks of paper as an official government printer. [24]

Moore recalled an ‘acquaintanceship that grew slowly into what was to be the closest friendship of my life’, concluding ‘there are few men who have done so much, so modestly, for young living artists’.

With the coming of peace Gregory was acutely aware of the need to ‘redesign’ Britain itself and threw himself into the current of post-war modernism that recast the new Labour government’s popular welfare state as ‘Modern Britain’. Two schemes mark this moment of energy: his role in the foundation of the ICA in London in 1947 and the Gregory Fellowships in Leeds. Both involved his close friendship with Herbert Read.

The founders, Read, Roland Penrose, Peter Watson and Gregory intended to secure a space for exhibition and discussion beyond the claustrophobic atmosphere of the Royal Academy that would foreground modernist art at its best. The first landmark exhibition, largely organised by Penrose but with important contributions from Gregory was ‘40 Years of Modern Art’, for which Gregory, the ICA’s first Treasurer, printed the catalogue and guaranteed it against financial loss. A posthumous exhibition of a selection from his own impressive collection was staged in 1959 and introduced by Henry Moore.

But demonstrating his commitment to his Yorkshire roots (although by birth he was in fact Scots) his next significant initiative was to found the Gregory Fellowships in the Creative Arts at the University of Leeds in 1950. At this time Leeds had no Department of Fine Art, though there was a flourishing Department of English Literature under Bonamy Dobrée, another close friend of Herbert Read’s (and mentor of Richard Hoggart) and a regular contributor to the New English Weekly founded by Alfred Orage. [25] Dobrée bemoaned the lack of his students’ engagement with actual practising artists and poets (which had been actively encouraged by an earlier Vice Chancellor, Michael Sadler, but discontinued by his successor, James Bailey). [26]

The scheme had in fact been approved by the Council of the University during the war in 1943 but took seven years to come to fruition. Gregory covenanted annual funding for Fellowships in Painting, Sculpture and Poetry, the last being insisted on by Gregory, with the aim of bringing ‘younger artists into close touch with the youth of the country so that they might influence it’. [27]

Fig 6.

Penrose Annual 40, 1938

Designed by Jan Tschichold

By Gregory’s death in 1959, PLH had become one of the most well-respected publishers of high-end art books and technical journals in Britain.

Gregory was assisted by an Advisory Committee of Read, Dobrée, Henry Moore and T S Eliot and the funding ran for nine years. The Fellows had no commitments other than to pursue their own work and become involved with the academic community – not always successfully however. This was the first fully-funded ‘artist in residence’ scheme of any university campus in Britain and the inspiring model for later attempts. Recipients of the Gregory Fellowship in Fine Art have included Terry Frost, Maurice de Sausmarez, Hubert Dalwood, Paul Gopal-Chowdhury, Ainslie Yule, Alan Davie, Ken Armitage, Martin Froy, Quentin Bell and Trevor Bell. [28]

This important innovation coincided not only with the upsurge of creative writing and criticism in the Department of English (from which emerged a swelling number of socially committed poets, novelists, dramatists and critics, including Tony Harrison, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Richard Hoggart, Wole Soyinka, and attracted Geoffrey Hill to its teaching staff) but with the appointment of Harry Thubron to the Leeds College of Art where he introduced the Bauhaus inspired regime of Basic Design, a model for art schools subsequently. In 1952 Dobrée and Read also conspired to appoint the émigré Marxist Art Historian, Arnold Hauser, to give lectures in Art History to Humanities students and, with Sausmarez, lay the groundwork for a Department of Fine Art with the social history of art at its core. [29] Leeds thus generated an enviable reputation as a thriving centre of radical avant-garde practice, history and criticism in both the plastic arts and writing.

By Gregory’s death in 1959, PLH had become one of the most well-respected publishers of high-end art books and technical journals in Britain. It is not hard to conclude that PLH and its Directors had occupied a seminal place in both the encouragement and promotion of young avant-garde artists and photographers and the construction of a public for International, and especially, British modernist art from its publication of Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought Forms in 1901, through its engagement with Bauhaus innovations in art and design, [30] and Moore, Hepworth, Read in the immediate post WW2 period, to the ICA and Leeds University’s Gregory Fellows.

From Percy Lund’s merging of occult theory and innovative technological practice, through a way suggesting publicly accessible ‘spiritual’ meanings to Moore’s and Hepworth’s statuary in Herbert Read’s introductions, to practical institutional interventions in the national culture, PLH helped reshape Britain’s image of itself. It was both Yorkshire and universal, a joyous celebration of the cultural vigour of provincial life in an international context. It is an arresting irony, however, that the story of PLH almost failed to include Bradford’s most glorious modern exemplar, David Hockney. With not a little hauteur, they turned down the teenage Hockney’s proffered portfolio in 1953, as ‘not suitable for their class of work’ - and only just caught up with him at The Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1970. [31]

References

[1] A number of accessible online accounts of PLH have been a great help in preparing this paper. I have drawn on Valerie Holman’s Lund Humphries a short history (https://www.ashgate.com/default.aspx?page=5102) though this has now been superseded by A Short History of Lund Humphries edited by Lucy Myers at https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0996/9954/files/LH_History_booklet_final_for_website.pdf?793156472052 9927002. Steve Lightfoot’s biographical notes on Percy Lund have been invaluable at https://sites.google.com/site/leedsandbradfordstudios/home/percy-lund as has his timeline of PLH publications 1893-1921 which catalogues their Theosophical and practical photography editions at https://sites.google.com/site/leedsandbradfordstudios/home/percy-lund/publication-timeline. But I have benefited greatly from conversations with Charles Lubelski (who Steve Lightfoot put me in touch with) and the chance to read his typescript monograph on the history of PLH, ‘Pride, Passion and Printing’ (which is in urgent need of a publisher). His corrections and clarifications to an initial draft were invaluable. Charles served an apprenticeship as a printer in Leeds and went on to become a lecturer in the subject. His understanding of PLH from the point of view of a print worker and compositor is invaluable and his account is very much Bradford rather than London-centred.

[2] Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London, Penguin Great Ideas, 2008.

[3] John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

[4] Christopher Rawlence, The Missing Reel: The Untold Story of the Lost Inventor of Moving Pictures. London, Collins, 1990

[5] Many thanks to Leeds historian, Janet Douglas for her inquiries.

[6] Read claimed his intellectual coming of age to have been at the Leeds Arts Club before WW1. There he will have become familiar with Besant and Leadbeater’s ideas and will have seen Sadler’s Kandinsky abstract paintings. He will almost certainly have read Michael Sadler junior’s translation of Kandinsky’s Uber das Geistige, see Michael Paraskos ‘Herbert Read and Leeds’ in Herbert Read A British Vision of World Art. London, Lund Humphries, 1993: 25-33.

[7] Lightfoot, https://sites.google.com/site/leedsandbradfordstudios/home/percy-lund.

[8] Logie Barrow, Independent Spirits: Spiritualism and the English Plebeians, 1850-1910 (Historical Workshop), London, Routledge & Kegan Paul Books, 1986: 9.

[9] Barrow: 271-280.

[10] Marina Warner, Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media into the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, 2006: 259.

[11] Warner: 260.

[12] Warner: 263.

[13] See http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265487.

[14] Charles Lubelski, ‘Pride, Passion and Printing’, unpublished typescript, 2016.

[15] Susan Duxbury-Neumann, Little Germany: A History of Bradford's Germans. Bradford, 2015.

[16] http://www2.tate.org.uk/archivejourneys/historyhtml/people_dir_rothenstein.htm.

[17] Henry Moore, ‘Obituary: Mr E.C. Gregory’, Times, 19 February 1959, p.12. viewed at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/henry-moore-obituary-mr-ec-gregory- r1173023.

[18] Holman, Lund Humphries a short history.

[19] Holman, Lund Humphries a short history. David Mitchinson writes ‘The triumvirate of sculptor Henry Moore, art historian Herbert Read and printer/publisher Peter Gregory was one based on friendship, Yorkshire, and mutual respect. Read had been the earliest writer of a monograph on Moore. Printed by the Bradford-based firm of Lund Humphries, of which Gregory was both joint Managing Director and chief shareholder, this was brought out in 1934 by Anton Zwemmer, the London-based publisher. Read continued writing about Moore’s sculpture over the next thirty years while Gregory became Moore’s closest friend...Given the strong personal relationship between the three men it is not surprising that they should have cooperated in 1944 to produce Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, the most comprehensive book on Moore’s work to date and one that would lead over the following decades to a six-volume catalogue raisonné of his sculpture and later to seven volumes of his drawings...’ in Myers, A Short History: 29-30.

[20] Ben Read writes: ‘The Lund Humphries monographs started with Henry Moore in 1944. This set a format of listing works, plentiful illustrations, an artist’s own writings or comments plus a critical introduction by Herbert Read. This pioneer volume was followed by others on Paul Nash, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo. These had all been leading members of what Read had christened ‘A Nest of Gentle Artists’, living close to each other in Hampstead in the 1930s. The effect of these volumes was dramatic. As Patrick Heron commented to me once, ‘reputations are created outside, in the great outside world, and that book by Lund Humphries, by your father, on first Henry and then Ben went into the museum libraries of the world just as the world ended. . .’. In other words, the volumes were sent as missionary, propaganda statements; as the volumes came clunking through the international institutional letter boxes, they set out a claim that British artists were as worthy of the full monographic treatment as anything on Picasso, Matisse or other equivalent national artists. Due tribute must always be paid to Peter Gregory, the Managing Director of Lund Humphries, who gave the scheme his backing.’ In Myers, A Short History: 38-39.

[21] Lubelski, ‘Pride, Passion and Printing’: 48.

[22] Lubelski, ‘Pride, Passion and Printing’: 51. Cf Antony Bell, Eye Witness of an Era – Some Memories of Lund Humphries in the 1930s . Lund Humphries, Pamphlet: 1981.

[23] Lubelski notes: ‘to work on research project to develop nuclear weapons called Tube Alloys with Michael Clapham now at the Kynoch Press to develop a fine metal membrane with sufficiently fine mesh to separate uranium isotopes.’

[24] Lubelski: 68.

[25] A R Orage (1873-1934) was the editor first of The New Age, 1907-1922 and then The New English Weekly 1932-34, where he was regarded as the outstanding editor of his generation. A Yorkshireman, he had previously established the brilliant Leeds Arts Club in 1903 as one of the most exciting sites of modernist art and thought outside London, see Tom Steele, Alfred Orage and the Leeds Art Club, 1893–1923. Aldershot, Scolar Press, 1990 (reprinted by the Orage Press, London, 2009).

[26] Sir Michael Sadler (1861 – 1943) was Vice Chancellor of the University of Leeds 1911-1923. He brought to Leeds a stunning collection of modern art much of which he exhibited publicly at the University and the Leeds Arts Club where both Herbert Read and Henry Moore (then at Leeds School of Art) got their first sight of post- impressionist art. Sadler became one of Kandinsky’s earliest British collectors and patrons, having urgently travelled to Murnau to meet him in 1912. His son Michael Sadler Jr. (later Sadleir) swiftly translated Kandinsky’s theoretical text Uber da Geistige in der Kunst (1912) as The Art of Spiritual Harmony in 1914 (and republished by the Tate in 2006), in which Kandinsky makes clear his spiritualist affiliations.

[27] http://www.artbiogs.co.uk/2/organizations/gregory-fellowship.

[28] Ibid.

[29] See Tom Steele, ‘Circles of Modernism : Herbert Read, Arnold Hauser and the Emergence of Art History in Leeds ‘ in Michael Paraskos ed. Re-Reading Read : New Views on Herbert Read. London, Freedom Press, 2008: 112-119.

[30] According to Sixten Ringbom, Kandinsky still relied on his German translation of Thought Forms while a leading member of the Bauhaus in the 1920s, see Sixten Ringbom The Sounding Cosmos: A Study in the Spiritualism of Kandinsky and the Genesis of Abstract Painting. Abo Akademi, 1970: 62.

[31] Christopher Simon Sykes, Hockney: The Biography. London, Random House, 2017: 33. PLH did printed the catalogue for David Hockney paintings, prints and drawings, 1960-1970 at The Whitechapel Art Gallery, 2 April- 3 May 1970.