For most British artists of the twentieth century, the self-portrait has been a vehicle for presenting a very particular image of self. One need only think of the swagger in the self-portraits of William Orpen or Augustus John, the minute examination of likeness in those by Stanley Spencer or Lucian Freud, the concept of identity in David Hockney. Lowry, we might think, should therefore have something similar in his oeuvre. He is, after all, such an incredibly familiar figure to us. Living long, he was amply photographed and filmed, and these images have come to define our sense of him. See, there he goes down the street, a tallish elderly figure, with trilby and stick, the flaneur of the terraces and mills.

If we accept that one of the prime functions of a self portrait is to let the artist tell us something about himself, then with Lowry we are on difficult ground. With Lowry, finding out is never easy. His life is relatively well documented, yet his feelings about important events are difficult to tease out. His relationships with friends were often kept very much separate, and when those friends did eventually meet, they found they all seemed to know a subtly differing version of the man. Do we thus find out more from his paintings?

The only painted self portrait by Lowry in the generally accepted sense of the genre is his early self portrait of 1925 (Salford Museum and Art Gallery). A reasonable likeness of the young artist, he presents himself very simply, head and shoulders only, wearing a cap and overcoat. No frills, no devices, no props. There is a vulnerability in the gaze, maybe a desire to connect with us, but otherwise we are told very little.

Self Portrait of 1925 (Salford Museum and Art Gallery).

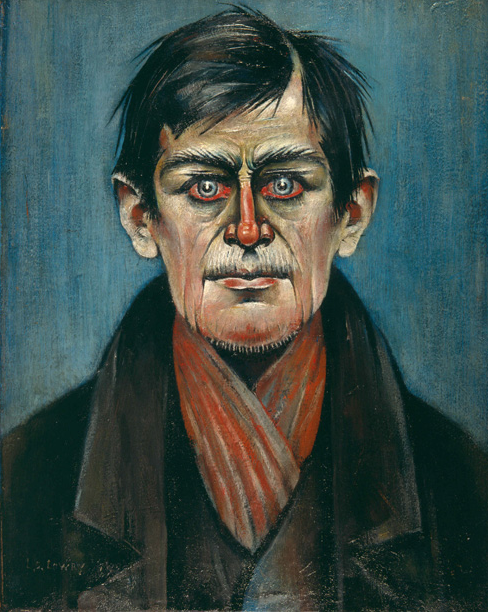

In the same year he produced a drawing, Self-portrait in a Mirror, Lytham St.Anne's (Salford Museum and Art Gallery) which shows the artist as he draws at a table, but all we see is the silhouette of his tall frame. He gives details for the rest of the room, the furniture, his father reading, the flowers in a jug in the table, but of himself we learn nothing. By the 1930s, his own image has become further submerged. The haggard, haunted Man with Red Eyes (Salford Museum and Art Gallery) of 1938 is an image of such direct correspondence with the viewer that it is almost hard to address.

Lowry later admitted that this lifesize head began as a self-portrait; "I was simply letting off steam" he declared. Yet even at a time when he was close to a breakdown, he could not leave it as himself, it's true nature had to be disguised; "I turned it into a grotesque head. I'm glad I did it, I like it better than a self-portrait."

"Dig beneath the surface of Lowry's art and it becomes clear these are not just paintings that depict a nostalgic view of the northern industrial landscape."

Dig beneath the surface of Lowry's art and it becomes clear these are not just paintings that depict a nostalgic view of the northern industrial landscape. These are works that will speak of greater things, should you want to hear. Throughout his life, Lowry had a very strong sense of what was proper to make public about ones own feelings and state and only in his later years was he prepared to shift that standpoint a little. Indeed it may well be that the effort of a lifetime of keeping up appearances began to be a burden for him. Inside the outer Lowry there is a man desperate to communicate. His output was prodigious, his narrative of the landscape and people of his life pouring on and on, canvas after canvas, drawing after drawing. The paintings are suffused with a mood that can be easy to dismiss as picture postcard nostalgia, but which is actually something much deeper. Lowry identifies himself so strongly with his world and environment that he can't help but paint his own identity into the work.

Yet as we noted above, rarely does he feel able to express this through a standard self-portrait. Instead we begin to see small elements appear in the pictures which we might interpret as such. Look closely at his street scenes and you will begin to see that often one figure stands out from the rest. Not always the same in dress or looks, nevertheless there is a consistent sense of slight awkwardness, of not quite fitting in. Sometimes this figure will progress across the canvas, other times he might stand and look out at us, the viewer, and will probably be the only character taking any notice of us, the only one who notices the audience beyond the footlights. As the years passed, this single figure becomes a little bolder, maybe just standing facing us, but still with the sense of an unbridgeable gap keeping us apart. Later still, he began to create images of tall standing rocks and pillars, such as self-portrait of 1966 (Private Collection), surrounded and assailed by the sea to which he finally attached the telltale tag.

"Look closely at his street scenes and you will begin to see that often one figure stands out from the rest."

So where does A Visit to Burton-on -Trent fit in? As is often Lowry's way, it is both clear and obscure. Although this is one of the very few occasions when he actually defines an image as a self-portrait, we are presented with a drawing which immediately removes one of the central tenets of the genre.

The central figure stands, facing away from us, at the far end of an alleyway. The walls of the alley, almost scoured into the paper with an incredible density of markmaking, shoot off with an exaggerated perspective that recalls images as diverse as expressionist film making and Bernini's Scala Regia in the Vatican. Beyond him, the way is closed, a dead end. As Lowry recalled in conversation with the writer Mervyn Levy, this is, in fact, a self-portrait and Levy illustrated this work in his book 'the drawings of L.S.Lowry' and further discussed it in the prelude. While he was in the town he found an unexpected passageway which he followed but which went "nowhere"! Thus we find ourselves with a very unusual form of self-portrait. The artist presents himself in the kind of stylised persona which identifies his own self very closely with the characters that people his paintings. This figure is seen only from behind, so the level of insight that he is giving us is immediately kept unclear, and the form of presentation is strongly reminiscent of a small group of other works by Lowry which, whilst not being directly identified as self-portrait images, are surely very indicative of his own selfimage.

These layers of obscurity do however seem to make connections with two groups of works very close in date to A Visit to Burton-on-Trent. In 1960, Lowry had produced a painting entitled A Late Caller (Private Collection) and a related drawing, The Christmas Eve Caller (Private Collection). Both images feature a silhouette of the upper half of a figure as seen through the window of a back door at night.

Lowry claimed that this related to an occasion when his doorbell rang late one Christmas Eve, and he saw a figure through the glass. However when he opened the door, there was no one to be seen. As the figure is presented in much the same way as Lowry's 'self' type in his wider work and how he presents himself in A Visit to Burton-on-Trent, then we must assume that this indicates that Lowry may have found a less than defined line between his own life, which was always a relatively solitary one, and that of his characters.

This is reinforced by Lowry's fascination with the play Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello, which he saw several times in a London revival starring Sir Ralph Richardson. In this remarkable play, the characters of an unfinished play confront their writer whilst he is in rehearsal for another play, demanding their story be finished. The concept that once the author had given an initial form to his characters they developed an independent 'life' appealed enormously to Lowry, and thus the blurring of lines between artist and creation must have been in mind when he created works such as The Christmas Eve Caller and A Visit to Burton-on-Trent.

Few British artists are as widely known yet largely misunderstood as Lowry. A deeply private man, his huge output over nearly seven decades is, once one begins to see it clearly, largely autobiographical, drawing on the life of a man whose sensibility was very much kept in check by the norms and manners of the lower middleclass Edwardian world in which he grew up.

Thus his art becomes his voice, and in a drawing such as A Visit to Burton-on-Trent it is a very powerful one.

"Few British artists are as widely known yet largely misunderstood as Lowry."